Play

Play

Writing Regina v Turing and Murray

- by Hwa Jung

Steven Downs wrote and directed the play. He explains his thought process and music choices. The music was arranged by Margaret Corlett, sung by the Vale Royal Singers with musical direction by Margaret Corlett.

When I was first approached to write and direct Regina v Turing and Murray in June, I was delighted but apprehensive. I had done similar projects in the past, but I’d had a ten year break from theatre projects, to work at my family’s iron foundry. Also the time scale was terrifying! I had just over a month to research and write a play about a man and situation I knew very little about. At the end of the month I had booked a fortnight’s holiday. When I returned from that, there was one more month to rehearse and get it ready. But it was a very interesting and challenging project, and I was wanting to get back to theatre work…so how could I possibly turn it down?

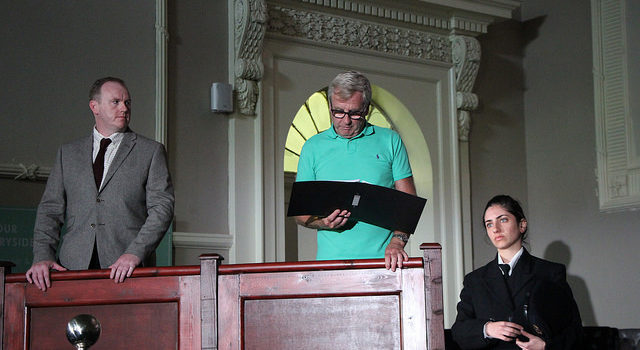

My brief was to write a play, of about forty minutes, based on the court appearance of Alan Turing and Arnold Murray at the Knutsford Crown Court, to be performed in the very room that it actually happened. I had done similar site specific projects in the past, and loved them! There is something very special about re-creating situations in the actual space where they took place. Indeed, during rehearsals, several people have told me that they had a moment when they suddenly realised that the events we are re-creating were real!

The framework of the story was to be the court appearance, however, because it wasn’t a trial, the accused pleaded Guilty, there was no conflict inherent in the story. This is not a good situation for a writer! So, how to introduce conflict was an important factor, because drama is conflict!

It was decided that we should have some surreal scenes, to break up the dryness of the court procedures. A choir was mentioned, this made me prick up my ears, again in the past I’ve used live music in productions, voices, drums, bagpipes and a didgeridoo!! Music really lifts a play, so this was exciting!

But first, research. That was days of reading books about Turing, one by Dermott, his nephew. Andrew Hodges wrote a 700 pages book about Turing which is incredibly detailed. Also, Sara, his mother wrote a short book following Alan’s death. In addition, there were articles online and TV programmes on Youtube. For a two weeks I saturated myself in things Turing! All the time I was jotting notes, noticing certain aspects or key words and phrases which kept popping up in different places.

Then the most difficult part, after planning, thinking of what the surreal moments could possibly be, I had a rough idea drafted out, but now I had to actually start to write dialogue!

The court situation was a double-edged sword. On the one hand it provided me with a clear framework and story line. However, there is a strict protocol and tradition in Law Courts, and, although I have done Jury service, that only made me realise how little I knew. Time was moving on and I couldn’t spare time to visit a court. By chance I was due to have a lunch with some old school friends, one of them, Graham, is a retired Judge, I took the opportunity to ask him if he would mind me picking his brains. He seemed very interested and proved to be an absolutely invaluable source of information. I would draft scenes in the court and show them and he would say things like, “Oh no, a Barrister wouldn’t say that to a Judge!” Often the phrase “This isn’t America!” would be thrown at me, obviously the influence of film and television has skewed my perceptions of the British Legal System!

So, I had a firm framework, and I was confident that what I wrote within that framework was authentic…but what about these surreal moments?

I liked the idea of seeing much of it through Turing’s eyes. He didn’t think he should be there, he almost had a contempt for the court, thought the whole thing was a ridiculous charade. So, in his mind, when the judge enters he sees him as a pompous, overblown caricature. Why should we stand for him? What’s all this nonsense going on? He lampoons it, in his mind, by playing a vocal fanfare, Zadoc the Priest[1] a Coronation anthem.

One way of breaking the normality on the stage, waking up your audience, as it were, is to play around with syntax and make the characters speak in a different, non-naturalistic way. This is where I could use the descriptions of Turing which kept cropping up in books and TV programmes, all saying, generally, good things about him. Character references would be heard in court, colleagues spoke up for Turing. So instead of just giving their references normally I brought both on together and made them speak in unison and in a round, splitting sentences and sharing them, generally creating verbal mayhem. From Turing’s point of view, they are just phrases, jostling with one another, repeated, turned back to front, a chorus of phrases, praising him, attempting to mitigate his actions. But they are meaningless to him, because he doesn’t think his actions needed mitigation! It becomes a cacophony of unnecessary praise when the whole court joins in. It jolts the audience into thinking, What’s going on here?

I decided that Turing would have little time for the mundane wanderings of the court as he would be thinking of higher things. He notices the repeated, leaf patterns in the ornate plaster ceiling of the Courthouse. This takes him right out of the moment into his own world of phyllotaxis. We hear what he is thinking. The choir make the moment more surreal, they sing about phyllotaxis[2]. The lighting changes to a surreal green. Suddenly the Judge cuts across all this, asking Turing if he is alright, thus nudging him out of his reverie.

But why just Turing’s inner thoughts? Murray needs a voice too. He is very much the minor character, but his thoughts are just as valid. He clearly regretted his actions, so to the strains of Who’s Sorry Now[3] a record he probably played on a juke box in a coffee bar down the Oxford Road, he gives us his take on the relationship.

Turing had a very unusual and not entirely comfortable relationship with his Mother. She was not at the Court, but I thought we needed to both see and hear her. Again she pops out of Turing’s head into the Courtroom. Those of you who have read John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, may remember the dream rabbit that keeps popping out of Lennie’s head to reprimand him. That is what inspired Sara’s appearance, to Stabat Mater Dolorosa[4], the grieving Mother stands by.

We share in Turing’s anger when the Judge accuses him of betraying his class. He is angry but his anger does him no good, it just exacerbates his despair. Like the Doleful Dove[5] the choir sings about, which pecks at its own breast until the blood flows, it gasps and dies.

So, all these surreal moments are attempts to break up the dry formality of the Court. They were also written to provide points of view about Turing’s position and the wider LGBT situation of that time. But I needed something else to pull all the strands together and present the audience with both ancient and modern perceptions, slices of history which put everything into a context. That’s where the Usher came into the picture. A sort of Everyman who could be part of the 1952 action, but step out into modern times when necessary. For those students of drama, he is the Brechtian figure, he can drop his character and address the audience directly, to explain, commentate, enlighten. He was the final, surreal device that linked the court experience directly to the audience.

To write something public about so great a person, is a heavy burden. Whatever you do, you always wonder, what would Alan think about it? How presumptuous is it to write down what you believe people to be thinking? How far off the mark am I with this? But we have to take the chance, his story is so important to aspects of life today. So many lessons are to be learned from it, it will influence many lives in many different ways. That is why it is so important to tell the story, even if parts are flawed. That is what makes the task onerous but it is also what makes it an honour. I hope that it will affect you, then, the job is done!

[1] Zadoc The Priest – George Frederic Handel

A Coronation anthem written for the Coronation of George II, in 1727. It has been used at many subsequent Coronations as well as being the theme of the UEFA Champions league!

In the play it reflects Turing’s opinion that the whole Court case is overblown and ridiculous!

[2] Locus Iste – Anton Bruckner

A sacred motet, composed in 1869. The words have been changed to reflect the subject of Turing’s day dream:

PHYLLOTAXIS, A NATURAL SYMMETRY.

MORPHOGENISIS, A GROWING GEOMETRY.

CONTINUOUS SPIRALLING, GROWING PROCESS.

DYNAMIC? CHEMICAL? PERFECT SPIRALS.

CHAOTIC SWIRLING CREATES FORM.

TINY PATTERNS, BUILDING TO LARGER FORMS.

FIBONACCI! A FRACTAL, FACTUS EST!

[3] Who’s Sorry Now? – Snyder, Kalmar and Ruby

An early 1950’s classic, made famous by Connie Francis. Probably on Oxford Road, coffee bar juke boxes at the time!

[4] Stabat Mater Dolorosa – Pergolesi

A 13th Century Catholic hymn to Mary, which portrays her suffering as Jesus Christ’s Mother during his crucifixion. Again, a little hyperbole!

Translated it means “The sorrowful Mother was standing”.

[5] Like as the Doleful Dove – Thomas Tallis

The words of this ancient piece of church music seemed particularly appropriate to Alan Turing in his current situation:

“Like as the doleful dove delights alone to be

And doth refuse the bloomed branch, choosing the leafless tree,

Where on wailing his chance, his bitter tears besprent,

Doth, with his bill his tender breast oft pierce and all to rent;

Whose grievous groanings though, whose grips of pining pain,

Whose ghastly looks, whose bloody streams outflowing from each vein,

Whose falling from the tree, whose panting on the ground,

Examples be of mine estate, though there appear no wound!”

1 COMMENT

This is a great read Steven – you really pulled it out of the bag on this one. You also wrote a couple of great monologues for the VR element which worked great and added another layer to the narrative. Hats of to you.

Comments are closed.